The Cost Of Lake Okeechobee's Runoff And The Impact On Southwest Florida's Water And Wallet

Jose Lopez, a 15-year resident of Cape Coral, can't let his grandchildren kayak in the canal behind his house anymore. What was once "clear, inviting water" is now often a murky, foul-smelling soup, with a "persistent foul odor, like rotten eggs". He worries about the risk of skin rashes and the 10-15% dip his real estate agent says his canal-front property value has taken.

Lopez's story is not unique. It is a personal snapshot of a "cycle of ecological and economic distress" gripping Southwest Florida, fueled by a decades-old water management problem: the nutrient-polluted discharges from Lake Okeechobee.

The problem, which re-ignites with every rainy season, is a man-made crisis with a staggering price tag. According to Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation (2024), in February 2024 alone, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released over 40.73 billion gallons of nutrient-rich lake water into the Caloosahatchee Estuary. These releases are the primary fuel for massive harmful algal blooms (HABs), like the devastating 2018 event that cost the region an estimated $2.62 billion in lost tourism revenue and forced Lee County to spend millions cleaning up over 400,000 gallons of toxic blue-green algae from its waterways.

Now, as 2025 comes to a close, this story seeks to determine the tangible, on-the-ground consequences of these discharge strategies. For the residents, scientists, and business owners on the front lines, it's a battle for their livelihood and the future of the Gulf Coast.

The Ecological Collapse

The environmental toll begins in the estuary, a delicate nursery where fresh water from the Caloosahatchee River meets the salt water of the Gulf of Mexico.

"The ecological impact is severe," says Dr. Eric Milbrandt, the Marine Laboratory Director at the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation (SCCF).

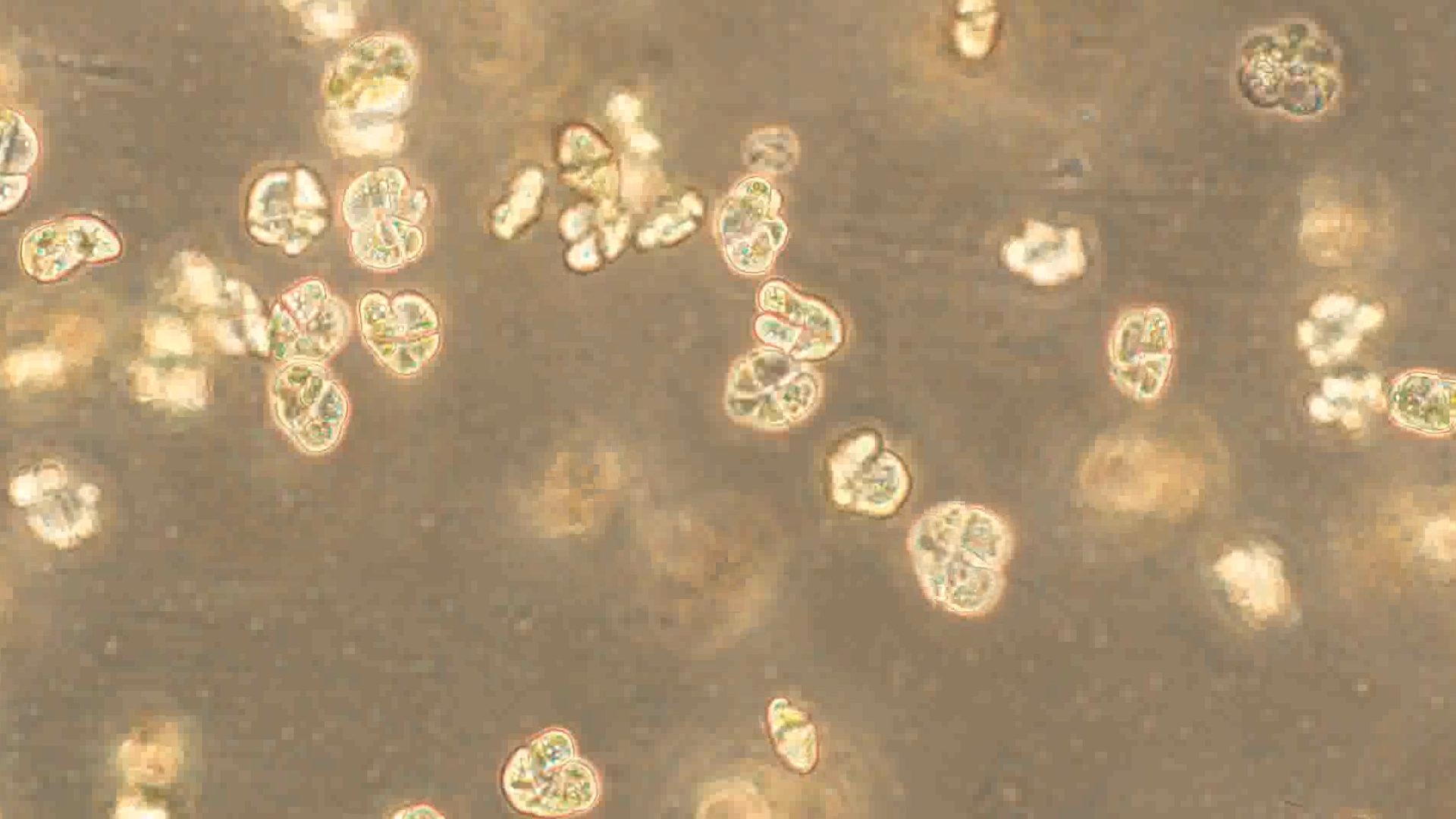

In his video interview, Dr. Milbrandt explains that the massive influx of polluted freshwater from the lake disrupts the estuary's essential salinity balance. This "bad water" carries high nutrient loads, primarily nitrogen and phosphorus, which act as a fertilizer for algae.

This process delivers a devastating "one-two punch": it fuels toxic blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) blooms in the river and, when that nutrient-rich water flows offshore, it provides the food for red tide (Karenia brevis) blooms in the Gulf. The resulting devastation includes widespread fish kills, the loss of vital seagrass beds, and long-term harm to the entire marine food web.

The Business of Bad Water

The environmental crisis translates directly into an economic one for an area where income is "directly tied to the health of the local environment and tourism".

Chris Davison, owner of the historic Island Inn on Sanibel Island, has seen the impact firsthand.

"When the water is bad, the phones stop ringing," Davison states in his interview. He describes the wave of cancellations and alarming media reports that follow a major bloom, crippling the hospitality industry. For hotels, restaurants, fishing guides, and watersport rental companies, the blooms are not just an eyesore; they are an existential threat.

This economic damage ripples far beyond the beaches, infecting the region's core financial systems.

Kyle DeCicco, President and CEO of Sanibel Captiva Community Bank, sees the crisis from a different-but-related perspective. "So much of our market down here is driven by... second homes... or investment properties," DeCicco explains in an audio interview.

When water quality events happen, he witnesses "a complete stop to real estate transactions". This uncertainty creates a dangerous domino effect.

"People need... financial... help," he says, noting that the bank receives requests from businesses for more money to get through the hard times, or even for "payment relief" on their existing loans. It's not just hoteliers, DeCicco points out, but also their employees who "might lose their jobs" and then struggle to pay their own mortgages, demonstrating how the toxic water flows through every sector of the local economy.

A System-Wide Failure

Florida then and now water flow with captions - infographic by Keys Weekly

The source of the pain for residents like Jose Lopez and businesses like the Island Inn is a "significant pressure" from nutrient pollution, according to John Cassani, the Calusa Waterkeeper Emeritus.

While Lake Okeechobee discharges are the most visible trigger, Cassani explains the problem is systemic, with pollution coming from two main sources: upstream and local.

"From our extensive water sampling, key sources include leaking underground sewer infrastructure," he says, pointing to "extraordinarily high fecal bacteria levels" in local tributaries like Billy's Creek in Fort Myers. This local pollution, from aging pipes, failing septic systems, and urban stormwater runoff, is a constant problem.

This baseline pollution is then exacerbated by agricultural nutrient loads from the watershed north of the lake.

When the Army Corps of Engineers releases lake water for flood control, as they did in November 2024 to lower the lake by four feet, it's like "pouring gasoline on a fire." This decision, often made to protect the aging Herbert Hoover Dike, unleashes a torrent of nutrient-laden water into an already-stressed local system, which is sometimes "already greening up" on its own.

The journey of the pollution is a key part of the story. Water from the Kissimmee River basin flows into Lake Okeechobee. To prevent the dike from failing, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) must release this excess water. While some goes south, massive volumes are sent east to the St. Lucie Estuary and west down the C-43 canal, the Caloosahatchee River.

This "water management" decision dumps high-nutrient, low-salinity water directly into the Southwest Florida estuary, bypassing the natural filtering capabilities of the Everglades and fueling the toxic cycle.

Infographic by Jim Cessna - created with Canva

A Search for Solutions

Solutions are complex, expensive, and slow-moving.

Progress is being made on the massive Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) Reservoir, a project designed to store, treat, and ultimately send more water south to the Everglades, restoring a more natural flow. Governor DeSantis's 2025-26 budget also invested $1.4 billion in Everglades restoration, which could eventually benefit the entire downstream system.

But experts say more immediate, targeted actions are critical. Cassani argues for mandating "water quality treatment components" for existing reservoirs like the C-43 to filter nutrients and accelerating the transition from septic systems to centralized sewers in high-risk areas.

For resident Lose Lopez, the solutions can't come fast enough. He wants "stricter enforcement" on nutrient limits and "holding polluters accountable with fines".

The fight is personal, but Cassani, who has been an ecologist in Lee County since 1978, remains hopeful. He is "encouraged by growing public awareness" and the science-based approaches that can, and must, restore balance.

For the residents and business owners of Southwest Florida, "hope" is a critical, but dwindling, resource. They are caught in a cycle of "toxic blooms poisoning a dream". The health of their economy, their environment, and their families is inextricably linked to the health of the water.

Until the flow of pollutants is truly stopped, not just diverted, they will continue to pay the high cost of a crisis that washes up on their shores, season after season.

Join the Conversation

Follow the ongoing policy debates, scientific updates, and community efforts to restore Southwest Florida's water quality via the Captains for Clean Water official Facebook page.